Wyjscie

The following piece, in a Polish translation, is published within the catalogue for an exhibition of my grandmother’s work currently being held at the Biuro Wystaw art gallery in Warsaw.

*

In my grandmother’s work room, behind her table, is a large wooden drawer chest filled with her life’s work. The curators of this exhibition spent countless days combing through those heavy shelves, a journey leading them through her different eras: dry point, charcoal, drawings of pen and pencil. Near the end of this journey, on a day when the curators were just leaving, I arrived and after exchanging greetings with them at the door, I stepped into the work room and saw something on the table that stopped me. “Oh. Babcia. I love this. But what is this?” She followed me into the room and began laughing. “Really?” she said. “You too?”

She explained that the curators had just found this work inside one of the last drawers, hidden between sheets of unused, blank paper. And they had wondered the same things, asking her what it was, but she couldn’t tell them. She couldn’t remember the work at all — when she’d started it or what she’d planned or why she’d stopped. But now here it was, on the table: this beginning. This old, new beginning.

For several days then, the paper rested off to the side as my grandmother, Maria Luszczkiewicz-Jastrzebska, worked on something else. She didn’t put it away, back in the drawer, because she had found the whole thing such a curiosity and wanted to see if the drawing may begin to talk to her, tell her what to do.

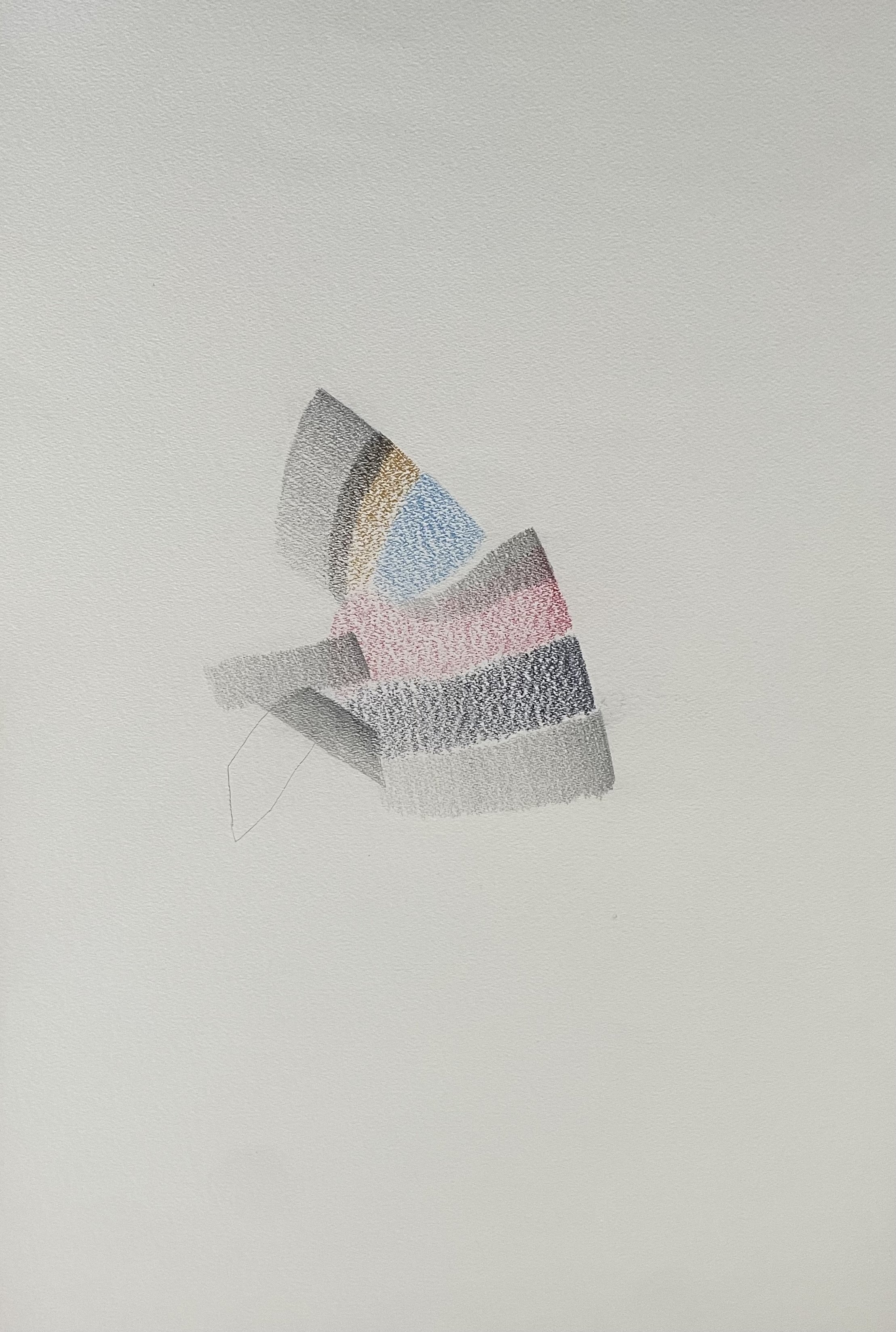

I offered that I loved it exactly how it was — just these few shapes and colors, floating inside of so much white. There was some poetry in this. And maybe the piece could be left as it was found, a kind of ode to beginnings, or potential. Or imagination. She, however, felt like something should be added. But what?

“Maybe I could add some flowers down here at the bottom, or around it,” she wondered, looking at it. “Or maybe not. Maybe that would be too much. It needs to be something that would add something, yet somehow I need to leave this beginning part, so it won’t be forgotten. This beginning should be the most important.”

Later, after some lunch, she said suddenly, “Oh. I could also just surround it with gray, to contrast the colors of the center. Because those colors are good…”

I always love when my grandmother is like this, in her element, inside of some work. And she says to me all the time that when she’s working she’s the happiest, because other things — things like back pains or politics — simply fade away when she’s focused, when a pencil is in her hand, and anyway, she then said, still thinking about the drawing: “It’s enough to do something wrong now. Because even then you can work from there, from a mistake, and find some answer.”

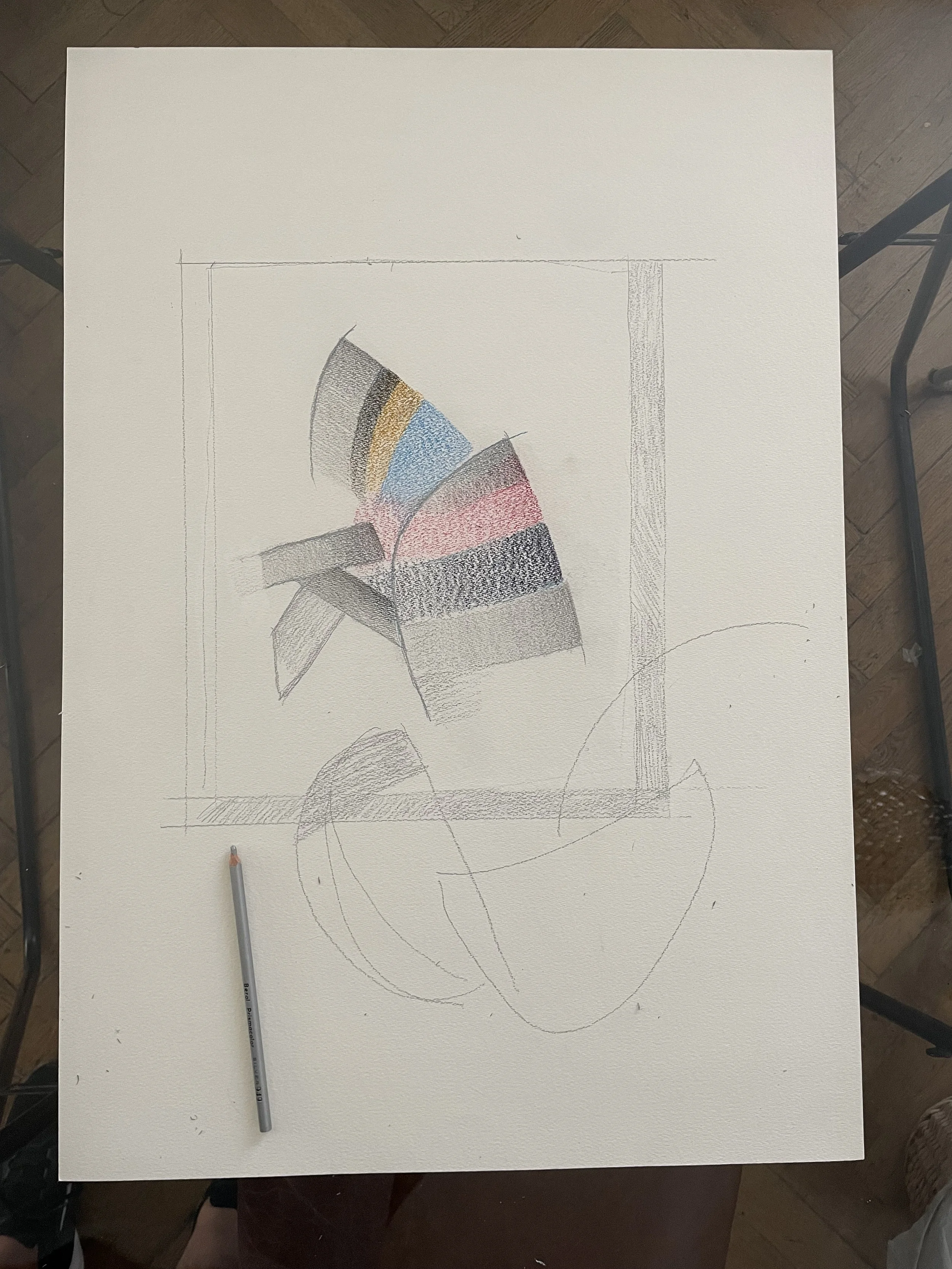

A few days later I came to the flat and was met with silence, my grandmother not calling out or meeting me at the door. I always know what this means, and sure enough when I went to the doorway of her work room I found her silhouette there, sitting at her table, working. I smiled, because this image always makes me smile. And when I came closer I saw she was now working on the drawing. She had added in the beginnings of a frame around those colored shapes, and was also now penciling in some other forms at the bottom.

“But I don’t know if it’s right,” she said, leaning away, considering it.

Two days later, on Easter Sunday, I arrived again and now found the work alone on the table, and again the drawing had changed: mostly gone were those shapes she’d added at the bottom, and instead there was a more full, more colored in frame around the discovered center. “Maybe this is enough?” she asked, walking into the room.

I asked her about the traces of old changes and erasures still visible on the paper — looking close, the eye clearly sees remnants of pencil strokes or coloring tried but later erased, though not fully. “Yes,” she said. “But maybe that’s OK. Because a drawing is a living thing.” And imperfections, she says, can make something more real, more alive.

When asked to write about my grandmother for this exhibition, I found this one drawing, this forgotten beginning, a good symbol through which to write about Maria Jastrzebska. This one work is a testament to the creative process — her process even visible through those lines and colors almost but not entirely erased — and it also contains some of the signature elements of her style that speak to me: movement, and translucence. My favorite works of hers are always the ones where I feel as if the elements inside are somehow in motion, and where the translucence of her colors or even her grays offer the eye a kind of way through, as if a further world exists somewhere there behind. Because, as she often says, in any situation — in life, or in a work of art — there is always a wyjscie, a way through.

Throughout my life, my grandmother has taught me such lessons. First when I began visiting Poland as a child from my home in America, and now as an adult, helping to look after her here in Warsaw. We enjoy comparing notes on our creative pursuits, her drawings and my writings. There are more similarities than differences, and often many of the same questions or problems. And always there is that moment when the words or work on a piece of paper begin to talk back, begin to tell the hand what to do. This is what we wait for. This is when a work begins to breathe.

Two of the closest figures in my grandmother’s life — her husband, the photojournalist Jan Jastrzebski, and her daughter and my mother, the artist Anna Gajewska — are no longer with us. But I feel so lucky to have grown up in such an artistic family, to have learned to view the world with their eyes: always photographing this world around us, and really trying to take in its miracles and wonder. On any walk with my grandmother she will marvel at the beauty of leaves, of little flowers, of how colors mix. She will stop in front of advertisements and consider their design. She will notice how people dress. She views every aspect of life through the lens of a composition, and when she’s at home working, she tries to compose something of herself on every next piece of paper, putting down whatever she is feeling.

“I simply draw my emotions,” she says. And if the shapes or colors there happen to later find someone and move them in any way, well then she finds this whole dance a kind of happy accident, a surprise, a curiosity. Another wyjscie, or way through.

*

Prawie cisza (Almost silence), an exhibition of the works of Maria Luszczkiewicz-Jastrzebska and Ada Adu Raczka, is currently being held at the Biuro Wystaw gallery in Warsaw. The gallery is located at Krakowskie Przedmiescie 16/18, and is open Wednesdays through Fridays from 12-6 p.m.